Patina by Prinsen: Nicola Prinsen sculpts irresistible animals

Patina by Prinsen: Nicola Prinsen sculpts irresistible animals

Nicola Prinsen knows visitors to the White Rock Gallery are going to find it hard not to pet her bronze calf.

The appealing little critter, thigh high, just cries out for a pat of comfort.

“That’s good,” she said during a recent visit to the gallery.

“The oils are good for the patina.”

The pettability factor is a tribute to her skills as a sculptor which seem to breathe life into both her realistic and her stylized work.

But, the affable sculptor, quick to see the humour in any situation, also feels a great affinity for her creations.

“I miss these guys You get used to having them around.”

And she has them around in her Saltspring Island home, a converted 1926 “big old dairy barn” complete with its original cowstalls and milking stanchions on the lower floor, where she has a 1,200-sq.-ft. studio.

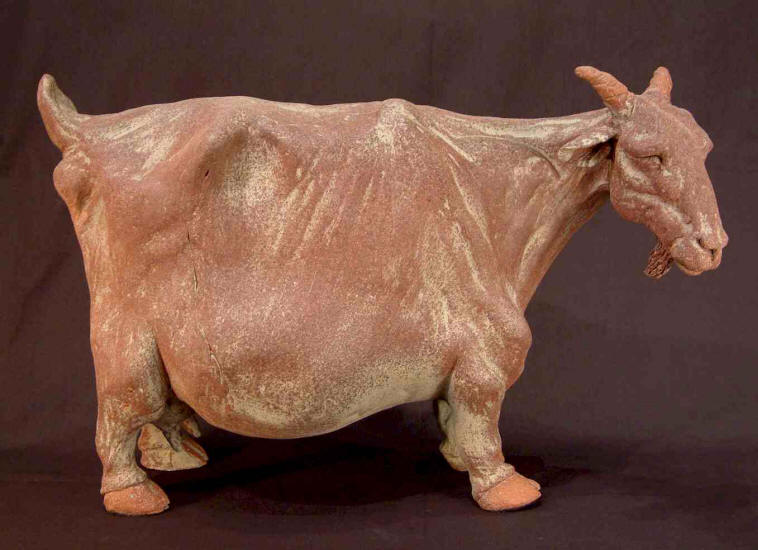

“I’ve had sheep in the living room and we’ve been thinking about taking the cow upstairs,” she said, referring to a life-size clay sculpture she has previously presented at the gallery.

Prinsen, who grew up around horses and other animals in Surrey-Langley, still finds them a central presence in her art, even though she has done some figurative sculpture in the past.

“Saltspring is very rural,” she said.

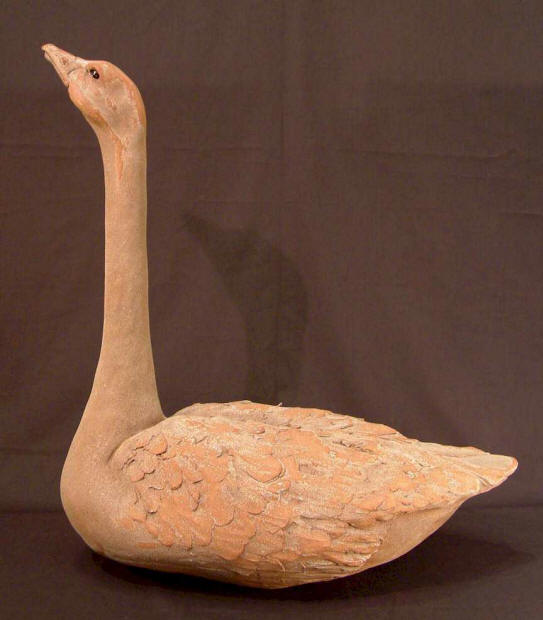

“As an artist, you tend to take inspiration from the things around you, and I’m surrounded by sheep and cows and crows.”

“All three have found their way into her upcoming show at the gallery, featuring original fired clay pieces and limited edition bronze pieces.

“Cows in particular,” Prinsen said.

“I like their form, their outline. I’m not finished with cows, by any means.”

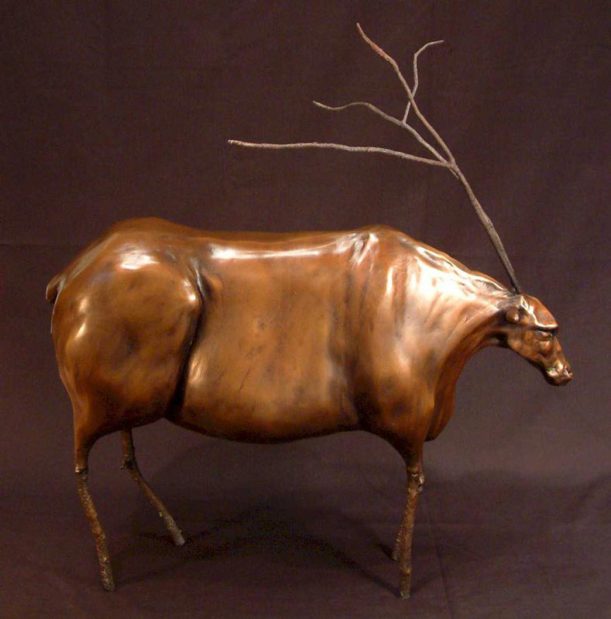

She points to another bronze in which the form of the cow has been distorted to the point of caricature, albeit sympathetic.

“My exercise is to go as far as I can until someone says ‘what is it?’

“Right now they’re saying cow — that’s a good thing.”

New to her menagerie are rabbits, which she has depicted in varying forms of stylization.

“I call this one Fast Bunny, she said, pointing to a galloping rabbit.

“This one evolved after that, so I called it Fast Bunny II.

“You try to stretch, try to simplify. Simple is a hard thing, harder than anatomically correct.”

Another sculpture, she calls it Laughing Horse, rests on its rounded, distended chest — a result of an experiment to create a rocking figure.

Others, like her caribou, have used sticks for stylized legs and antlers.

Some larger clay pieces would be impractical to turn into bronzes, Prinsen said, given the logistics of casting bronze in the lost wax process, which requires urethane rubber moulds made from a clay original, an outer shell, and complicated armatures.

The upper limits of size are tested by her calf — which may weigh as much as 375 pounds.

“She is hollow-cast bronze,” Prinsen said.

“If she were solid, she’d be closer to 2,000 pounds. Usually for fine art casting, you’re doing a hollow core.”

That creates its own set of challenges, she said, including ensuring the majority of the sculpture is of equal thickness.

“If you have a lot of different thicknesses, the thinner stuff cools faster — and then it twists,” she said, pointing to the calf’s head.

“Her nose is probably quite solid, though.”

She can never quite escape the fanciful.

“The magical thing about bronze is that you can defy gravity with it,” she said.

“If you wanted her to be on one leg, she could be on one leg.”

The upcoming show is an unusually large collection for a sculptor to exhibit at one time, Prinsen acknowledged, and represents a year of quite intense work.

And even though it can become quite addictive, she said — what she refers to as ‘the bronze bite’ — she’s looking forward to some time off.

“After the show, I’ll need to take a break. It’s been a long haul.”

Fortunately she has an understanding and supportive partner, Vern, with a master’s degree in arts from Concordia University.

“He used to do my moulds for me. Now he feels I’ve enough experience to do them myself.”

Prinsen admits the intensity of the work has a lot to do with her endless experimenting with finishes and colour patinas on the alive surfaces of pieces like her rabbits and crows — and the endless structural challenges she throws out to the bronze casters she works with.

She’s always been aware of her desire to push boundaries.

“I started when I was 22 at the University of Alberta in the ceramics department. I was doing wheel-thrown forms, I’d take them off the wheel and squish them up. People would say ‘Are you sure you’re not in the wrong department?’

“When I was three, my mom sat me down and told me ‘All across Canada there are square holes — and you’re a round peg’,” she laughed.

“I didn’t know what she was talking about. I said ‘OK’. I think I thought it was a compliment.”